Okay, so I admit it, when I first heard that a graphic novel (in layperson's terminology, read: comic book) illustrator/writer had illustrated

Jane Eyre, I was somewhat taken aback. I mean - "comic books" and "

Jane Eyre" don't exactly roll off the tongue together! But, ever the optimist, I bought and opened the illustrated version. And, frankly, had to put it down to go get a very large piece of humble pie. Not only did the illustrations look fine, they worked. Essentially, what Dame Darcy has done is to usher

Jane Eyre into the modern world through her graphic, yet Gothic, artwork. Brilliant! It's akin to the discovery the Reese's company made when they put chocolate and peanut butter together. Of course, not everyone thinks so...naturally, when you take an established classic and do anything to it that reeks of modernity, someone is going to raise a stink. Read on to find out more about the book, Dame Darcy, and the controversy...

DAME DARCY ON "THE ILLUSTRATED JANE EYRE" by Jonah Weiland, Executive Producer Posted: August 15, 2006 — More From This Author

The novel "Jane Eyre" by Charlotte Brontë remains one of the most famous and influential novels of all time, continuously adapted over the years to a variety of mediums whether it be the 1996 film starring Anna Paquin or the upcoming BBC mini-series. It's the story of one woman and the adventure life takes her on from her youth as a poor orphan haunted by visions, to the woman she grows into and the challenges she faces during that journey. It's a story filled with tragedy, love and strength that has inspired artists and writers for over a century and a half. Dame Darcy is just one of many who've been influenced by "Jane Eyre." Her gothic/neo-Victorian artistic style has been hailed by many, including the New York Times who said, "Darcy's comics are aesthetic manifestos… Darcy is a star." The creator of Fantagraphics' "Meat Cake" as well as a member of the band Death By Doll will shortly bring her unique artistic style to the pages of "The Illustrated Jane Erye," an illustrated novel from Viking Studio, an imprint of Penguin Books. The book is the perfect pairing of words and art as it reprints Brontë's original story accompanied by hundreds of Darcy's illustrations. The book sees publication September 21st. CBR News spoke with Darcy by phone last week about the book and why she was attracted to this project.

Darcy discovered she had fans at Penguin through her work on "Meat Cake." In 2003, Darcy completed her graphic novel "Gasoline" and asked her literary agents to shop it around. As they pitched it around town, they discovered that Penguin was doing a classics series and were interested in having Darcy illustrate "Jane Eyre." "I was so elated by that news - it's one of the best things that's ever happened to me in my life," Darcy told CBR News. "I really love 'Jane Eyre' as a classic feminist novel, but also I'd like to do other ones in the future, like 'Wuthering Heights.' I hope this one goes well so that I can do that one.

"It's weird because Jane's psychology is really interesting," continued Darcy. "She approaches feminism in a really different way than I do, but I'm really glad that someone in the 1840s was feminist and was writing stuff like this and that it's lived on to today. It can still apply to today's world. It's a classic for a reason."

|  |

Illustrating "Jane Eyre" took Darcy almost two years, beginning work on it in 2004 and finishing in 2005. She explained she was left to choose which elements of the story she felt were worth bringing to life with her illustrations. "When I was reading the book I'd choose those scenes that felt the most visual to me," said Darcy. "That's usually how it works with all my freelance work. Someone will hire me to illustrate a book or an article for a magazine or paper, I'll read it and then whatever scene comes to my mind is what I'll sketch out and send to the client. Once they approve it, I'll finish it up. People usually don't ask me to change that much or have a problem with what I pick. I'd say 90% of the time people are pretty chill with my choices."

Darcy was first exposed to "Jane Eyre" while in art school where it had an immediate impact on her. "It's just so gothic and awesome. I really like how all this surreal weird stuff goes down, while the rest of the time is spent drinking tea and staring out the window - which I think is actually kind of cool. I enjoy doing that, too! [laughs]"

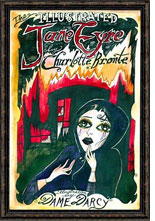

Penguin gave Darcy a lot of room to play with in working on "The Illustrated Jane Eyre" and every illustration she created for the book will see print. "What's really great is they asked me to do the cover and it could have been any image from the entire book, but I thought the way to make it really kind of punk rock for the new generation of goth girls that it'll appeal to was to take the scene where Jane Eyre is freaking out while the giant mansion is burning behind and Jane Eyre is written in bloody red letters. That's how hard core Jane Eyre gets! People think it's this classic about a governess, but it's not necessarily about that - I mean, she gets called a witch about 7000 times and everything demented and tragic goes down during the book. I thought that should be portrayed. Plus, she's seriously Catholic-damaged, which is probably true for most of my fan base. [laughs]"

Darcy described the process she went through to illustrate the novel. "I draw everything in pencil and once I get the pencils approved I'll go and ink them," said Darcy. "After that I'll paint over top. Lately I've been doing this thing where I paint with acrylics, but I water them down to use them as water colors because I want them opaque or translucent depending on the need. When they dry, I put this kind of sepia tone wash over the top to make them look a little older. Now, you can't do that and still have a water color effect with water colors, but you can with the acrylics."

Darcy described the process she went through to illustrate the novel. "I draw everything in pencil and once I get the pencils approved I'll go and ink them," said Darcy. "After that I'll paint over top. Lately I've been doing this thing where I paint with acrylics, but I water them down to use them as water colors because I want them opaque or translucent depending on the need. When they dry, I put this kind of sepia tone wash over the top to make them look a little older. Now, you can't do that and still have a water color effect with water colors, but you can with the acrylics."

While hundreds of illustrations accompany the book, there is one scene in particular that Darcy enjoyed illustrating the most. "There's one piece where Jane has had a dream, and in the dream she saw the burnt down mansion and the full moon rising over the top and bats were living in the burnt down mansion and she's holding a crying baby and is just staring at it. That's my favorite one, I think. I think it captured what dreams are like."

Article available on-line: http://www.comicbookresources.com/news/newsitem.cgi?id=8140

*******************************************************************************

book blitz: All about fiction.

Governess Gone Goth: A new edition of Jane Eyre reveals its truly subversive message.

By Ann HulbertPosted Thursday, Oct. 12, 2006, at 10:08 AM ET

Judged by its cover, the Viking Studio/Penguin Group's new The Illustrated Jane Eyre might well make a grown-up reader bridle: What is this, a great book decked out for the Goth-teen crowd? A hefty paperback with flaps, its demure spine is done up to look just like a scuffed leather-bound first edition, while the campy cover was drawn by underground comic-book artist Dame Darcy, whose neo-Victorian, funky, Addams-family-style creations have won her a cult following. Aiming to make the novel look "really kind of punk rock for the new generation of goth girls," she picked "the scene where Jane Eyre is freaking out while the giant mansion is burning behind," Darcy explained to an interviewer. In a black cape and hood, her huge eyes heavy with kohl, a pale-faced Jane weeps while orange flames jag upward and blood-red letters spell out the title in the black sky. The back cover, where you might expect some reminder of Brontë, features a sepia photograph of Dame Darcy instead. She poses in the decadently frilly fashions she has made her signature garb.

Judged by its cover, the Viking Studio/Penguin Group's new The Illustrated Jane Eyre might well make a grown-up reader bridle: What is this, a great book decked out for the Goth-teen crowd? A hefty paperback with flaps, its demure spine is done up to look just like a scuffed leather-bound first edition, while the campy cover was drawn by underground comic-book artist Dame Darcy, whose neo-Victorian, funky, Addams-family-style creations have won her a cult following. Aiming to make the novel look "really kind of punk rock for the new generation of goth girls," she picked "the scene where Jane Eyre is freaking out while the giant mansion is burning behind," Darcy explained to an interviewer. In a black cape and hood, her huge eyes heavy with kohl, a pale-faced Jane weeps while orange flames jag upward and blood-red letters spell out the title in the black sky. The back cover, where you might expect some reminder of Brontë, features a sepia photograph of Dame Darcy instead. She poses in the decadently frilly fashions she has made her signature garb.

But since when should a book—especially a book by Charlotte Brontë—be judged by its cover? Brontë's guiding insight into life and literature, to simplify only somewhat, is that surfaces are suspect: Beware of assuming they are a reliable sign of the real passions within. Her own title page in 1847 (a facsimile of which appears in the Viking edition) was purposely misleading: Brontë adopted the male-sounding pseudonym of an editor named "Currer Bell" and presented the novel as an "autobiography." This immediately sparked debate about the real identity of the author. Subsequent biographical treatments of Brontë only added to the gallery of mythic personas. And of course, Brontë's most famous character, the "Quakerish governess" Jane, is a prime case of deceptive packaging herself. Out of a "poor, obscure, plain, and little" victim emerges a commanding—and demanding—narrative voice, proclaiming a right to bold self-creation almost as jarring today as it was a century and a half ago. A mistreated orphan at the start, Jane goes on to script her own dramatic fate—and to alter the destiny of her "master," Mr. Rochester, who falls under her spell. In a story tricked out as a melodramatic romance, Jane embodies a force that still deeply discomfits us: a female refusal to be valued as less than an equal, which blossoms into a fierce ambition to make her mark on the world.

For alienated Goth girls drawn to the macabre whimsy of the Dame Darcy edition (which contains 40 illustrations), a surprise therefore awaits. What is spookiest about Jane Eyre is not that it taps into fantasies of craggy-featured lovers and ghoulish horrors, but that it endorses desires for creative dominance, as Jane lights her own way from dependency to heretical authority. By now, the bats-and-bloodstained-petticoats stuff, a staple of dark comics, has minimal power to shock. Even in the staid days when Jane Eyre first caused a sensation, parents who hid the book were worried about more than the racy luridness—disturbing though that was. ("The love-scenes," one stunned reviewer wrote, "glow with a fire as fierce as that of Sappho, and somewhat more fuliginous.") It was the bold "I" expressing herself on every page, and the outsized imagination behind it, that had Jane Eyre's original audience truly alarmed, as the fevered speculation about the reality behind Currer Bell reveals: Who, reviewers wondered, would dare conjure up a female capable of speaking with such "a clear, distinct, decisive style," such "hardness, coarseness, and freedom of expression," such "power, breadth, and shrewdness"?

For alienated Goth girls drawn to the macabre whimsy of the Dame Darcy edition (which contains 40 illustrations), a surprise therefore awaits. What is spookiest about Jane Eyre is not that it taps into fantasies of craggy-featured lovers and ghoulish horrors, but that it endorses desires for creative dominance, as Jane lights her own way from dependency to heretical authority. By now, the bats-and-bloodstained-petticoats stuff, a staple of dark comics, has minimal power to shock. Even in the staid days when Jane Eyre first caused a sensation, parents who hid the book were worried about more than the racy luridness—disturbing though that was. ("The love-scenes," one stunned reviewer wrote, "glow with a fire as fierce as that of Sappho, and somewhat more fuliginous.") It was the bold "I" expressing herself on every page, and the outsized imagination behind it, that had Jane Eyre's original audience truly alarmed, as the fevered speculation about the reality behind Currer Bell reveals: Who, reviewers wondered, would dare conjure up a female capable of speaking with such "a clear, distinct, decisive style," such "hardness, coarseness, and freedom of expression," such "power, breadth, and shrewdness"?

You might think that by now such a declaration of feminine independence would have lost its subversive force. Yet it's precisely that uninhibited voice that still gives Jane Eyre its power. I'm not sure the outspoken "I" looms quite so large for adults as for children; on revisiting Jane Eyre, an older reader may be distracted by assorted kinky undercurrents his or her 13-year-old self missed completely. But for adolescents approaching the novel as a classic (its days as illicit fare are long since over), the immediacy of address is startling. Within the first few pages, Jane the marginalized victim has already begun taking revenge, pinning her brutal aunt and cousins to the page with a merciless ear and eye—"I mused on the disgusting and ugly appearance of him who would presently deal [the blow]." She is the deeply intimidating child on whom nothing is lost.

In an era when everybody—from the Girl Scouts to guidance counselors to the Gossip Girl series—peddles the "you-go-girl" message, Jane Eyre is a book that evokes the struggle for self-definition as a truly harrowing one. This isn't a coming-of-age story about absorbing the counsel of wise mentors, overcoming temptation, and thus learning to "be yourself." As Edward Mendelson astutely observes of the novel in The Things That Matter, Jane sets about doing something much lonelier and harder. She insists on finding "her beliefs by herself," in her own way, as she weathers exile after exile, first from her past (a hellish home and school) and then from a future that seems, fleetingly, to await her with Rochester. She doesn't come to accept others' values as her own, as the protagonist of the traditional novel of education does. Instead, "[w]hat Jane learns," Mendelson writes, "is not how to act, but how to believe."

Such a quest is a creative ordeal that demands self-reliance and an inner core of confidence to embark on in the first place. I know I'm not alone in having subliminally assumed that Jane Eyre was a portrait of the artist as a young woman when I first read it (which I would swear I did huddled, Jane-style, on a window seat behind a curtain—except that my parents' house had no such perch). And when you think about it, I was right. Jane isn't just a frail governess who ends up a wife and mother, happily ever after; she is also a published author, both within the "fiction" of the novel (narrated to us) and as a reflection of its real author, Charlotte. Brontë, remember, called the book an "autobiography" as a ploy to push readers closer to her lowly narrator—but also as a gesture toward the truth. Brontë, who at 20 sent poems to the poet laureate and told him she yearned "to be for ever known," channeled her own unbounded literary ambition into Jane, who refuses to be treated as a marginal figure. In turn, the indomitable Jane has a way of enlisting her readers, especially the adolescents among them, in the dream of being recognized as an assertive original.

"Reader, I married him"—the often cited opening sentence of the novel's conclusion—is a line that has yet to lose its galvanic power. There is, of course, that decisive "I," where you would expect a demurer and more domestic "we." But it is Jane's confident invocation of "Reader" there that is truly thrilling. She is claiming the status of a writer—and, more, the authority of someone able to command an attentive audience, not just of intimates. In closing, the former outcast asserts that hers is a voice worthy of being listened to beyond the hearth, a voice that might spur others on to a triumphant path.

Dame Darcy is not the first, nor the last, to heed that voice and fall under the heady spell of Brontë's ambition. Just look at her assuming center stage in that photo on the back cover, and listen to her on her MySpace page, where she rallies her Goth-girl fan base to her latest production: "Calling all Bats! (and fairies, we mustnt forget the light) The Halloween season is drawing nigh and with it comes the Dame Darcy's Bi-Costal tour! Yes! BOTH COASTS of the good Ol' USA. I will be signing my latest graphic novel The Illustrated Jane Eyre, Published by Putnam Penguin." In her own mind, the cult queen of the alt-comics/zine universe has evidently usurped the author's place. It's an act of creative presumption that Brontë—who fought her way up from the fringe herself—would probably forgive, especially if it helps get the book on the bats' radar.

Review available on-line: http://www.slate.com/id/2151318

***********************************************************************************

Review: Michelle Boule,

MLS The Illustrated Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Illustrations by Dame Darcy

This book has been sitting on my desk for about two and a half weeks waiting to be reviewed, so Slate beat me to the punch. Their review is quite nice, so feel free to go read it as well.

This volume belongs in the library of any Bronte aficionado. There are many things which will endear this book to its readers. After the title page of this volume, a replica of the title page from the original first edition appears with the author appearing as Currer Bell, the name under which Charlotte Bronte wrote Jane Eyre. The original foreword by the author to the second edition is also included and was a joy to read. The pages are rough cut, like folio pages. All of this would have been enough to make this bibliophile swoon, but then there are also illustrations.

The illustrations, of course, are what make this a truly lovely volume. Dame Darcy, of whom I had not previously heard, has created drawings that are gothic, dark, and playful. They reminded me a bit of Edward Gorey, though Dame Darcy has a style all her own. Most of the illustrations are in black and white, but there are some very wonderful ones in color. Some of the drawings are full page depictions of the novel’s events and others grace the margins. Dame Darcy is able to show both the bleakness of the human condition always present in Bronte’s work while also including the notion of hope that the characters hold for the future.

It has been a few years since I delved into Jane Eyre and this beautiful rendition of a much loved book, makes me want to romp on the hills of the Rochester Estate once more.

Highly Recommended – Great for Charlotte Bronte newbies and essential for lovers of the original

This entry was posted on Saturday, October 14th, 2006 at 4:24 pm and is filed under

book reviews.

Available on-line: http://wanderingeyre.com/2006/10/14/book-review-the-illustrated-jane-eyre/

**********************************************************************************

The Little Professor: Things Victorian and Academic

October 15, 2006

In yet another attempt to sex up Jane Eyre, Penguin has released the Illustrated Jane Eyre; the illustrations in question come courtesy of Dame Darcy. While I've not yet seen this new edition, there's some moderately irate discussion on the VICTORIA list about Ann Hulbert's article at Slate. Presumably, Hulbert cannot be blamed for the article's subtitle--"A new edition of Jane Eyre reveals its truly subversive message"--which, in the space of a short sentence, manages to claim that a) readers were unable to pick up the "message" on their own before this new marketing coup, b) the message thus kindly "revealed" to us is the true one, and c) the true message in question is somehow "subversive." (Of what? Has anything been subverted? If so, shouldn't we have noticed by now?) As one VICTORIAnist points out, however, It's a little harder to forgive either Hulbert or, indeed, Viking/Penguin for failing to notice that Dame Darcy misremembered the novel: "Aiming to make the novel look 'really kind of punk rock for the new generation of goth girls,' she picked 'the scene where Jane Eyre is freaking out while the giant mansion is burning behind,' Darcy explained to an interviewer." And what scene would that be? Perhaps this is what some critics call a "symptomatic" mistake--rather like confusing Frankenstein and his creature. In any event, the Jane on the front cover looks like a Goth Little Red Ridinghood (black hood, of course, not red); one wonders just how big Rochester's teeth are.

Hulbert rightly observes that "Brontë's guiding insight into life and literature, to simplify only somewhat, is that surfaces are suspect: Beware of assuming they are a reliable sign of the real passions within." And she is also right to observe the strength and verve of Jane's speaking voice. But her excited rush to claim the novel as a "declaration of feminine independence" leads her to trample that voice's complexity, as well as its moments of self-critique. In a sense, and probably inadvertently, Hulbert writes in post-Gilbert & Gubar mode, with Jane as the very model of a major proto-feminist speaker. Perhaps that explains Hulbert's ringing account of the novel's conclusion: "In closing, the former outcast asserts that hers is a voice worthy of being listened to beyond the hearth, a voice that might spur others on to a triumphant path." Yet the novel quite famously does not conclude with Jane at all, but with St. John Rivers, on his way to an apparently glorious death in the course of his missionary work. (Another symptomatic mistake?) Jane, meanwhile, happily settles down in ultra-remote Ferndean. The voice may travel, but down what sort of path?

More problematically, Hulbert gives in to the siren song of biographical interpretation:

Jane isn't just a frail governess who ends up a wife and mother, happily ever after; she is also a published author, both within the "fiction" of the novel (narrated to us) and as a reflection of its real author, Charlotte. Brontë, remember, called the book an "autobiography" as a ploy to push readers closer to her lowly narrator—but also as a gesture toward the truth. Brontë, who at 20 sent poems to the poet laureate and told him she yearned "to be for ever known," channeled her own unbounded literary ambition into Jane, who refuses to be treated as a marginal figure. In turn, the indomitable Jane has a way of enlisting her readers, especially the adolescents among them, in the dream of being recognized as an assertive original.

Now, I don't mean to trample on Dan Green's territory here, but as critical responses to Jane Eyre and Jane Eyre go, this one is reductive--and traditionally so, as Lucasta Miller has shown. It's fair enough to say that Jane yearns to be "recognized as an assertive original," but problematic to argue that she is a "reflection" of Brontë, let alone of Brontë's "unbounded literary ambition." (Again, that Brontë had "unbounded literary imagination" is also fair enough--and I suspect that, contra Hulbert, she would be unamused at finding herself displaced by her illustrator.) And while Jane does indeed need "self-reliance and an inner core of confidence," as Hulbert says elsewhere, there's no mention in the essay of whence it derives: a slightly idiosyncratic and universalist Protestant faith. Like Gilbert & Gubar, and unlike more recent critics like Maria LaMonaca, Kathryn Sutherland, and Marianne Thormahlen, Hulbert skates over the novel's Christianity--even though Jane's faith is an integral part of her passion. Whatever else Jane Eyre is, it isn't a secular self-help book for teenagers, Goths or otherwise. Whether or not it can be read--or illustrated--as one is, of course, a different matter entirely.

Available on-line:

http://littleprofessor.typepad.com/the_little_professor/2006/10/jane_eyre_goths.html

************************************************************************************

Dame Darcy's webpage: http://www.damedarcy.com